Labor & Workers in the Food System

Sustainable food must be produced in a way that takes not only the environment and consumers into account, but also the people who grow, harvest and process it.

Reprinted with permission; condensed from a longer article on FoodPrint.org

Current methods of production of crops like corn and soybeans rely heavily on machinery. But for raising and processing fruits, vegetables, meat and poultry, the agriculture industry still relies primarily on human labor. Farm and food workers are mainly an immigrant workforce, many of whom are undocumented. They are often poorly paid and work in harsh or dangerous conditions. This is just the latest chapter in a long history: the US was built on exploitative agricultural labor that dates back to slavery. Today, however, some of the most successful worker-organizing strategies are emerging from the fields, as farm and food workers fight for their rights and dignity.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF US FARM & FOOD LABOR

The struggles of today’s food and farmworkers are not new. Since the earliest US history, agricultural workers have been a disenfranchised group, often brought against their will and denied the right to vote once in the US. A brief examination of a history of US farm labor shows that it is inseparable from a history of state-sponsored racism.

In the 1600s, indentured servants were brought from England to work as field laborers in exchange for their passage to the so-called New World. When farm labor demand began to outstrip the supply of willing servants, land owners expanded the African slave trade, developing an economy reliant on the labor of enslaved people kidnapped from Africa. The practice continued legally for 200 years, enriching businesses in both North and South, until the end of the Civil War.

Following the prohibition of slavery, the white power structure passed the Jim Crow laws of the 1890s, institutionalizing discrimination and ensuring that cruel treatment of African-Americans would continue for decades to come. Many former slaves and their descendants continued working in the fields sharecropping, often in conditions not notably better than enslavement.

Meanwhile, farming was becoming big business and the US turned to workers from China, Japan and the Philippines to meet the demand for labor — until the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act led growers to increasingly turn to labor from Mexico.

INDUSTRIALIZATION OF AGRICULTURE & LABOR DEMANDS

INDUSTRIALIZATION OF AGRICULTURE & LABOR DEMANDS

As agriculture became more industrialized, related sectors like food processing did as well. The horrors of the rapidly-expanding meatpacking industry were revealed in Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle, and subsequent public outcry and union organizing brought about food safety laws and greatly improved worker conditions in meatpacking plants.

During the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, many white farmers were forced to sell or abandon their farms and become migrant workers. With these white farmers now in need of work, a half million Mexican-Americans were deported or pressured to leave. A package of important labor laws protecting worker rights also passed in this period, but they excluded farmworkers and domestic laborers. Not coincidentally, these jobs were most commonly held by African-Americans and immigrants.

A series of temporary guest worker programs began in the 1940s. The most well-known of these, the Bracero program, recruited workers from Mexico. It was eventually ended due to widespread worker abuses and wage theft. Organizing by the United Farm Workers (UFW) contributed to the program’s end. Founded by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, the UFW united Filipino and Mexico workers in a movement that brought national attention to the struggles of workers in California fields – and built models still used by farmworker organizers today.

FARM AND FOOD WORKERS TODAY

Today, immigrants produce the majority of our food, from farms to processing plants to restaurants and grocery stores. Wages are low, conditions are often harsh or dangerous, and immigrants not legally allowed to work in the US are often afraid to report abuses for fear of deportation.

As of 2014, 80% of US farmworkers were Hispanic, which included 68% born in Mexico and 27% born in the US. The foreign-born farmworkers interviewed had been in the US an average of 18 years, and 53% were authorized to work. Farmworkers’ median annual farm incomes in the previous year were just over $17,000.

The 47% of farmworkers who are undocumented and not authorized to work — and the many similar workers in meatpacking plants and elsewhere across the food chain — face struggles. While most federal and state labor laws, including those regarding wages and safety training, protect all workers equally, regardless of immigration status, many undocumented workers either do not know these rights or are afraid to assert them.

Even in an environment of increasingly hardline immigration enforcement, the produce industry is worried about labor shortages — and so it is investing heavily in automation. Robots that can plant, weed and even harvest delicate fruits and vegetables are already working in some fields and facilities, and rapid technological innovation means they will likely become much more common in coming years.

DANGEROUS WORKING CONDITIONS

Whether in vegetable fields or meatpacking plants, farm and food workers face hard, often dangerous working conditions.

CONDITIONS IN THE FIELDS

Planting and harvesting crops involves repetitive motions, often being stooped or bent for many hours, lifting heavy buckets of produce and operating machinery that can lead to injuries. The work is performed outdoors in hot weather, often without shade or adequate water.

Breaks are infrequent. Sometimes workers are punished for taking a bathroom break, and the common method of paying workers by the piece penalizes those who do take breaks, because they’ll make less money. Workers often face nausea, dizziness, heat exhaustion, dehydration and heat stroke, which is the leading cause of farmworker death.

Farmworkers are also regularly exposed to toxic chemicals from applying pesticides or herbicides (often done without adequate protection), from handling produce that has been recently sprayed, or, in some instances, from being directly in the path of a pesticide application. And many female farmworkers are sexually harassed and abused by their supervisors or other workers. Wage theft is also standard practice.

CONDITIONS ON FACTORY FARMS

Conditions at concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), also known as factory farms, are no better. Gases from manure pits including hydrogen sulfide, ammonia and methane fill the air, along with dust and irritants known as endotoxins.

One quarter of CAFO workers experience chronic bronchitis and nearly three quarters suffer from acute bronchitis during the year. Chronic exposure to hydrogen sulfide can cause brain damage and heart problems, and even at low levels can be deadly. Regular inhalation of particulate matter such as dust can cause both respiratory and heart problems, while high levels of ammonia can cause asphyxiation.

MEATPACKING PLANT CONDITIONS

For several decades of the mid-20th century, meatpacking jobs were some of the best paid in the manufacturing sector and lifted a diverse workforce into the middle class. Today, however, jobs in meat and poultry processing plants are some of the most dangerous and poorly compensated.

Workers kill, eviscerate and cut up thousands of animals every day, working in conditions that are humid, slippery, loud, hot or below freezing. Respiratory problems, skin infections and falls are common.

Work is determined by the speed of the processing line. Breaks are discouraged or denied, even for the bathroom.

On the fast-moving line, workers make the same cutting, pulling or hanging motions thousands of times a day; these repetitive motions cause crippling musculoskeletal injuries. Workers also wield sharp knives and work with fast-moving heavy machinery.

FOOD WORKER ORGANIZING

Throughout US history, agricultural and food workers have been some of the most exploited workers in the country. But they have also done some of the most powerful organizing. In the 1960s, United Farm Workers held large-scale strikes at the peak of the grape harvest to force higher wages from large farmers and formed a union to negotiate with growers over the long term. In meatpacking plants, unions such as the Congress of Industrial Organizations and the United Packinghouse Workers of America won better conditions, transforming those jobs for several decades into a secure path to the middle class.

In the last decade, at a time when union membership is at an all-time low and the labor movement has suffered many legislative and cultural defeats, some of the best worker organizing momentum continues to come from the fields and restaurant floors. When the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW), a group of immigrant tomato-pickers in Immokalee, Florida, had no luck getting the big tomato growers they worked for to meet demands for pay increases, CIW turned to the consumer instead. They enlisted student and faith organizations, demanding that the fast food companies that bought from those growers pay just a penny more per pound of tomatoes to give the workers a living wage.

This strategy has had remarkable success: after years of pressure, most major fast food companies and many supermarket chains have signed CIW’s Fair Food Agreement, pledging to buy tomatoes and certain other produce only from growers who meet labor standards.

Meanwhile, fast food workers across the US have led the campaign for a higher minimum wage in the Fight for 15. In just a few years, an hourly wage that in 2012 was too high to be called minimum – $15 per hour – was passed into law in states and cities around the country.

WORKERS ON THE FAMILY FARM

We recommend purchasing food whenever possible from local family-owned farms, which are generally better stewards of the land and water than large industrial farms. Labor, however, has all too often been overlooked by those interested in sustainable food and agriculture, so it is not a given that small-scale local farms necessarily have better labor standards than large industrialized farms.

Recent research has documented abuse, low wages, isolation and poor living conditions of workers even on some farms that sell at farmers’ markets, community supported agriculture programs, and farm-to-table restaurants. Those interested in sustainable food and agriculture must be as concerned about the people all along the food chain as we are about what goes into or onto the food.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Please visit foodprint.org for the full length version of this article including references.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

|

What You Can Do

For many years, the only label that addressed farm labor was the “fair trade” stamp — but it applied only to foreign products. Fortunately, in the last few years, more labor certification programs for US products have been developed for consumers who want to support not just good environmental practices, but also the rights and livelihoods of the people along the food chain.

- Food Justice Certification standards go beyond USDA organic certification to also guarantee just working conditions for workers and fair pricing for farmers. www.agriculturaljusticeproject.org

- Look for fast food restaurants and grocery stores that are part of the Fair Food Program, which guarantees fair treatment and wages for the farmworkers in their supply chain. www.fairfoodprogram.org

- RAISE (Restaurants Advancing Industry Standards in Employment) is a group of 300 restaurant owners who practice “high road” employment practices, (living wage, benefits, environmental sustainability). www.fairfoodprogram.org

- A growing number of cities are part of the Good Food Purchasing Program, which shifts institutional food purchases to a model that supports worker health, environmental sustainability, local economies, nutrition and animal welfare. www.foodchainworkers.org

Unfortunately, most food does not come with a label attesting to a farm’s labor practices. To support farm and food workers in more ways than with your purchasing power, check out the National Farm Worker Ministry, Coalition of Immokalee Workers or CATA (The Farmworker Support Committee). Many farmworker support organizations work locally; find out if there is a group in your state that you can support by volunteering, donating or advocating for policy change.

|

|

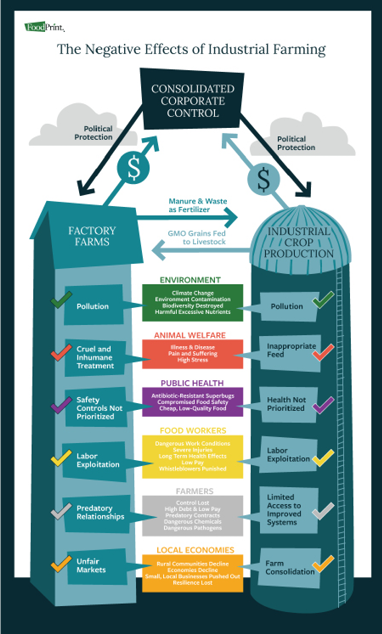

What is a FoodPrint?

Whether it’s a salad, a hamburger or your morning egg sandwich, your meal has an impact on the environment and on the welfare of animals, food/farm workers and on public health.

Your “foodprint” is the result of everything it takes to get your food from the farm to your plate. Many of those processes are invisible to consumers.

Industrial food production — including animal products like beef, pork, chicken and eggs and also crops — takes a tremendous toll on our soil, air and water, as well as on the workers and the surrounding communities.

Learn more about what a foodprint is and why you should care about yours at www.foodprint.org.

|

Industrial agriculture refers to the large-scale, intensive production of crops and animals, often involving chemical fertilizers and pesticides on crops or the routine, harmful use of antibiotics in animals (even when the animals are not sick).

Industrial agriculture refers to the large-scale, intensive production of crops and animals, often involving chemical fertilizers and pesticides on crops or the routine, harmful use of antibiotics in animals (even when the animals are not sick).

INDUSTRIALIZATION OF AGRICULTURE & LABOR DEMANDS

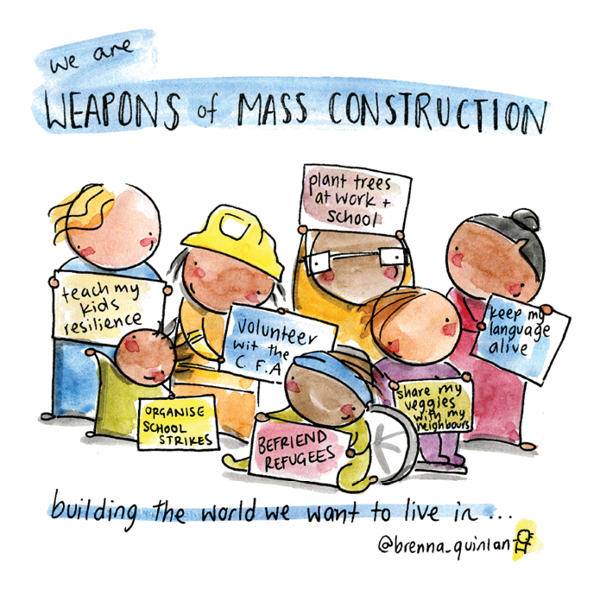

INDUSTRIALIZATION OF AGRICULTURE & LABOR DEMANDS At Cooperation Humboldt, we believe that access to nutritious and culturally appropriate food is a basic human right, and must not be denied to anyone regardless of income level.

At Cooperation Humboldt, we believe that access to nutritious and culturally appropriate food is a basic human right, and must not be denied to anyone regardless of income level.

GROW KNOWLEDGE & ANTI-RACIST PRACTICES

GROW KNOWLEDGE & ANTI-RACIST PRACTICES SUPPORT COMMUNITY-RUN COLLECTIVES

SUPPORT COMMUNITY-RUN COLLECTIVES