Regenerative Farm Spotlight:

Table Bluff and Alexandre Family Farms are flipping conventional farming perspectives one patch of soil at a time.

by Katie Rodriguez, Cooperation Humboldt

Pumpkin the pig at Table Bluff Farm / photo credit: Katie Rodriguez

Take a minute to imagine what healthy soil might look like – a teeming mecca of microorganisms and insects working together to process and cultivate important nutrients that help plants thrive. Think of it as akin to a rainforest underground, a complex ecosystem that’s integral to turning carbon (the villain of global warming) into a superpower fuel. Looking at the soil as an ecosystem that should be allowed the time, space and nutrients to function without being disrupted is at the core of what we know today as regenerative agriculture.

You may have heard this term before; it’s been touted as a carbon sink, the next “climate solution under our feet.” Regenerative agriculture fundamentally shifts our perspective from conventional farming methods to Indigenous farming methods – emphasizing that instead of thinking only of crop yields, we must also consider the condition and needs of the soil, and more broadly, the relationship between humankind and the diverse ecosystems at play.

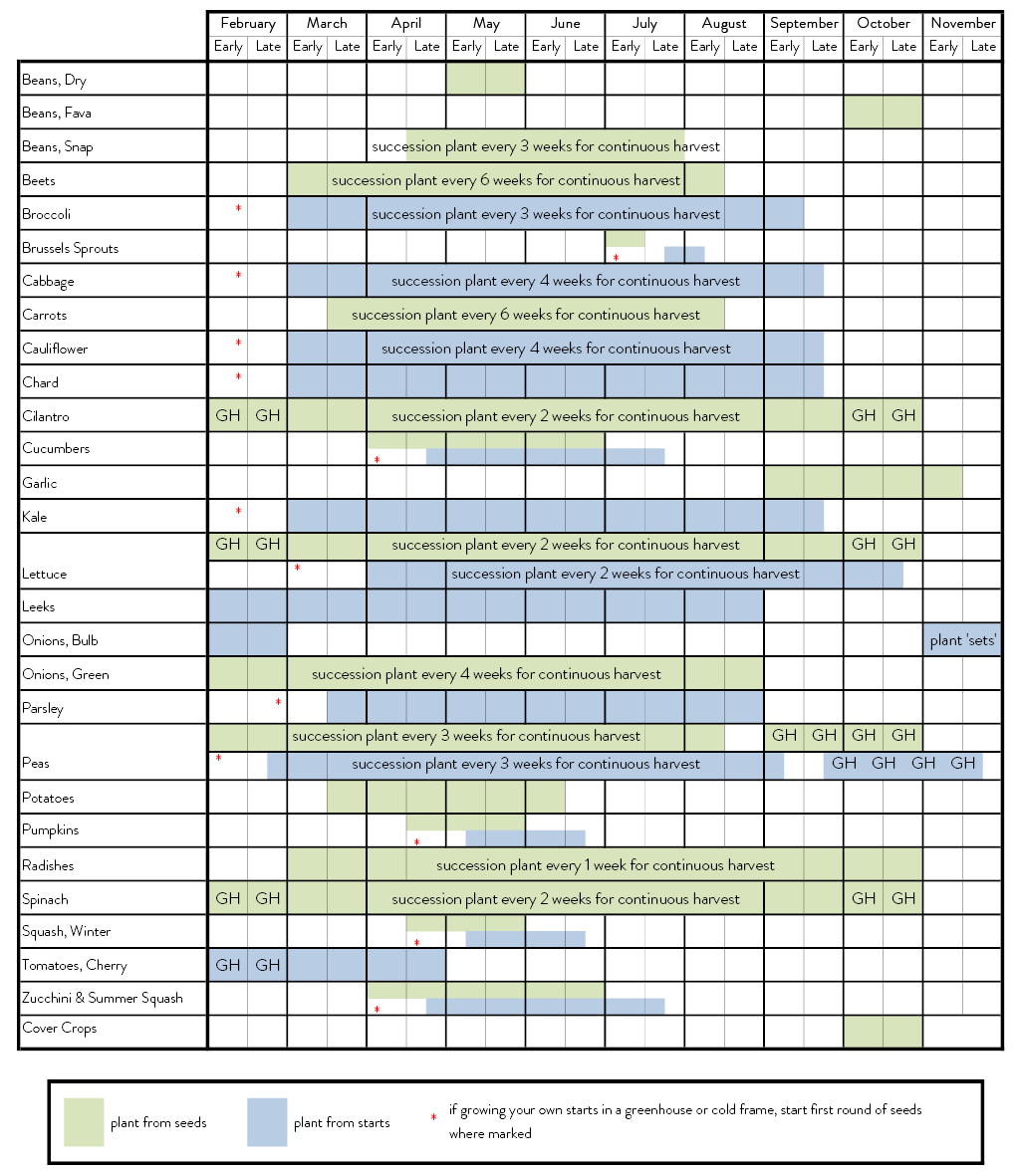

In practice, regenerative agriculture requires looking at a farm holistically. This involves utilizing things like cover crops to assist in suppressing weeds and soil diseases as well as fixing nitrogen and sequestering carbon; and integrating livestock by strategically moving them to graze and yes, poop (fertilize). It requires thoughtful time – observing how plants, animals, and insects can cohabitate with one another in a beneficial way, and encouraging that process. It also challenges a farming practice widely accepted for generations – routine plowing. No-till management with minimal disruption is key to allowing healthy soils to work their magic.

The benefits of regenerative agriculture – other than fertile soil – are many: no pesticide use, no supplemental fertilizers, little to no machinery and therefore, reduced machinery costs, no GMOs and increased carbon absorbed from our saturated atmospheres.

But can this be done on both a small and large scale? And what does that look like?

Hannah and Nic of Table Bluff Farm / photo credit: Katie Rodriguez

SMALL IS MIGHTY: TABLE BLUFF FARM

“There’s this idea that you need to have a lot of land to succeed [in farming] but that’s just not true” says Hannah Eisloeffel, owner of Table Bluff Farm.

Table Bluff Farm currently sits on about 2 acres nestled between the Eel River, the Pacific Ocean and the Humboldt Bay Wildlife Refuge in the town of Loleta. Today, the microfarm is managed and run entirely by Hannah and her partner Nic Pronsolino, and produces a variety of mixed vegetables, flowers, eggs, broilers, and heritage hogs.

They’ve come a long way in a short time, having only recently purchased the land in 2017. Back then, it was an overgrown horse pasture filled with blackberry brambles, ponderosa pine trees and acidified soil. Hannah and Nic have been busy – pouring their heart and resources into rehabilitating the land and turning it into the lush farmland it is today; now providing for a growing list of CSA members and other locals.

Hannah’s vision and mantra have been salient: prioritize the health of the soil and the health of the local community. From the farm’s conception, the mission has been rooted in following regenerative agriculture principles – both for restoring the necessary balance in nature, and to provide equitable access to their goods.

“We believe that to practice regenerative agriculture you also have to be regenerative for your community and the economy,” says Hannah. “Everyone has a right to good food. We want to make it easy for people to eat healthily and affordably.” And Hannah and Nic have done just that – providing their products for a low cost, and a true cost. Instead of requiring a large up-front cost for a year of CSA produce, they have a pay-as-you-go system: $20 per week for a box of seasonal veggies (or $25 with delivery included).

Their emphasis on practicing smaller-scale regenerative farming has garnered the support of organizations like the NRCS (Natural Resources Conservation Service), the CDFA (California Department of Food and Agriculture) and the nonprofit Kiss the Ground. Grants from these organizations have been instrumental to enacting projects like creating high tunnels to assist with weather management, installing drip irrigation and planting perennials such as redwood trees, monkey flowers, pink honeysuckle, six different species of berries and more. The presence of perennials is a huge component in capturing carbon because they are never harvested or disturbed, and they help protect other plants from wind.

Table Bluff Farm is the smallest farm to receive a grant from the Kiss the Ground Foundation, a nonprofit that supports farmers transitioning to a regenerative agriculture model. The reason? Replicability – enforcing the notion that following regenerative principles can happen on both small and large scales, and Table Bluff Farm was an excellent example of what that can look like.

Hannah’s story is an inspiring one for many reasons, but perhaps one of the most notable ones may be that as a first-generation farmer, she began her farming experience just five years ago in 2016. “I never dreamed that I would become a farmer, even though I can tell now from my whole life I had all these proclivities. I just never really thought that was an option for me.”

A 2008 environmental studies graduate from UC Santa Cruz, she’d used school to cultivate her knowledge and passion to pursue environmentally minded work, while maintaining a deep desire to get her hands dirty and learn more about what goes into creating a farm. After meeting her partner Nic, who shared some of his extensive farming background knowledge with Hannah, coupled with completing Darren J. Doherty’s Regrarian certificate program through Kiss the Ground’s Farmland Program, she took the leap of enacting her vision of creating Table Bluff Farm.

For more about Table Bluff Farm, visit tableblufffarm.com, or keep up to speed on Instagram at @table_bluff_farm.

Alexandre Family Farm cows are moved from pasture to pasture to graze on tall, healthy grass. The residual plant biomass decomposes, and helps keep carbon in the soil as particulate organic matter. / photo credit: Katie Rodriguez

A FAMILY AFFAIR: ALEXANDRE FAMILY FARM

For the Alexandre Family, dairy farming is in their DNA.

Blake and Stephanie Alexandre, both fourth-generation farmers, met while in school at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. Both of them, determined to carry on their family’s traditions, began searching for land to create a dairy farm of their own. Although their hearts were set on Ferndale, California, where Blake originally grew up, fate had a different plan. They landed in Crescent City about 29 ago, wowed by the landscape and falling more in love with the area the longer they stayed.

And so they remained. The Alexandre Family Farm today has expanded from 560 acres to 4,500+ acres, with over a hundred employees (including all five of Blake and Stephanie’s children), 4,200 cows, 35,000 hens and an organic alfalfa hay farm for animal feed. They sell their organic products – milk, cream, yogurt, beef, eggs, chicken and pork – all across the United States; and over the years they’ve worked to become a certified humane, organic, non-GMO, and regenerative farm.

For Stephanie and the Alexandre Family, what all of these titles boil down to is: nutrition. Good nutrition goes beyond platitudes or labels, it’s a necessary building block to life that has played a pivotal role in how the Alexandres live their lives and operate their farms. In their minds, you can only have good food if it comes from healthy animals and healthy soil. Prioritizing nutrition for themselves and their buyers translates to ensuring the best nutrition for their cattle, chickens, pastures, and environment.

When Stephanie and Blake first bought their land, they befriended an agronomist that taught them all about how to measure organic matter in the soil. It was akin to what they learned in school, that “if you want healthy plants, you really have to have a great soil biology happening and growing that organic matter,” Stephanie says.

And so they held true to that mantra. As they grew their farm, they spent the time and resources to understand what was happening underground, observing how it affects their pastures. They saw that their pastures with a higher percentage of organic matter led to greener fields for longer amounts of time – even with less irrigation or during colder weather.

They found that moving their animals around not only made for happier, healthier cows and chickens; it also created more organic matter in the soil – and so they began implementing rotational grazing as part of their farming practices to support the best soil biology and maximize grass pasture growth.

Twice a week, mobile chicken coops are moved to different parts of the farm as part of the Alexandre Family Farm’s rotational grazing strategy. / photo credit: Katie Rodriguez

“When the term regenerative got thrown around” shares Stephanie, “we were like ‘Well, that’s what we do. That’s what we’ve been doing for years, we’ve just been learning how to do it right’.”

Because of their efforts to improve ecosystem health, which includes the soil, animals, land, water and air, they are the first and only dairy to be verified by the Savory Institute, a global nonprofit enterprise that conducts research on soil health, biodiversity and ecosystem function. Additionally, they were one of 21 farms (and the only dairy farm) to be selected for the global Regenerative Organic Alliance pilot program, and one of only ten farms to receive designation as Regenerative Organic Certified at their 100% grassfed dairy in Eureka.

“We just want to be a light in the community,” shares Stephanie. “We didn’t do this to drive better cars or build a bigger house. We just wanted to tell the story of where great food should come from.”

To learn more about Alexandre Family Farm, visit alexandrefamilyfarm.com or on Instagram @alexandrefamilyfarm.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Katie Rodriguez (she/her) is a freelance writer and photographer based in Arcata. Much of her work focuses on scientific, cultural and natural elements, with the goal of illuminating the ways in which we can better care for our planet.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The way to stop climate change might be buried in 300 square feet of earth in the Venice neighborhood of Los Angeles, amid kale and potatoes. A half-dozen city youth are digging through the raised bed on a quiet side street, planting tomato seedlings between peach and lime trees. Nineteen-year-old Calvin sweats as he works the rake. There’s a lot at stake here. The formerly homeless youngsters are tentatively exploring farming through a community outreach program started by a California nonprofit called Kiss the Ground. More importantly, they are tending to the future of our planet.

The way to stop climate change might be buried in 300 square feet of earth in the Venice neighborhood of Los Angeles, amid kale and potatoes. A half-dozen city youth are digging through the raised bed on a quiet side street, planting tomato seedlings between peach and lime trees. Nineteen-year-old Calvin sweats as he works the rake. There’s a lot at stake here. The formerly homeless youngsters are tentatively exploring farming through a community outreach program started by a California nonprofit called Kiss the Ground. More importantly, they are tending to the future of our planet.

Stock pot recipes are an easy way to cook ahead for a busy week. They also allow you to buy seasonally, keeping recipes simple and affordable.

Stock pot recipes are an easy way to cook ahead for a busy week. They also allow you to buy seasonally, keeping recipes simple and affordable. To enjoy butterflies and bees in your surroundings, you need to do more than plant the flowers and other plants that they like. You must also adopt practices that foster a healthy ecosystem for all the critters—the native bees and beetles; the tiny crawlers in the soil; the birds. If you attract butterflies and bees with flowers, only to kill them with your yardwork, you could be doing more harm than good.

To enjoy butterflies and bees in your surroundings, you need to do more than plant the flowers and other plants that they like. You must also adopt practices that foster a healthy ecosystem for all the critters—the native bees and beetles; the tiny crawlers in the soil; the birds. If you attract butterflies and bees with flowers, only to kill them with your yardwork, you could be doing more harm than good.

LEAVE THE LEAVES

LEAVE THE LEAVES